Eric Bell and the Wild, Wounded Heart of Thin Lizzy

How One Guitarist Helped Shape a Band—and Soundtrack My Youth—Before Fame Took Over

I first heard Thin Lizzy on a hazy autumn evening in 1973, my freshman year of college. A few of us were radio junkies, all enrolled in a two-year broadcasting course, and obsessed with Portland’s newest curiosity on the FM dial: KQIV. It was a short-lived experiment in quadrophonic sound—four-channel radio — and didn’t have the best signal. But it had soul. It was free-form AOR before corporate playlists took over, and they played everything worth hearing: Zeppelin deep cuts, old blues, obscure psych tracks, and new bands just bubbling up from the underground.

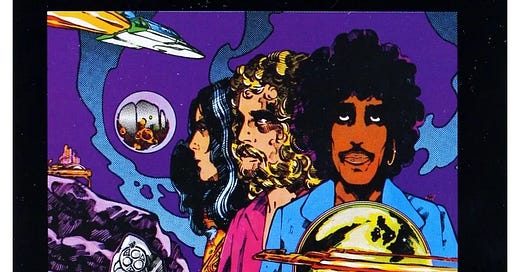

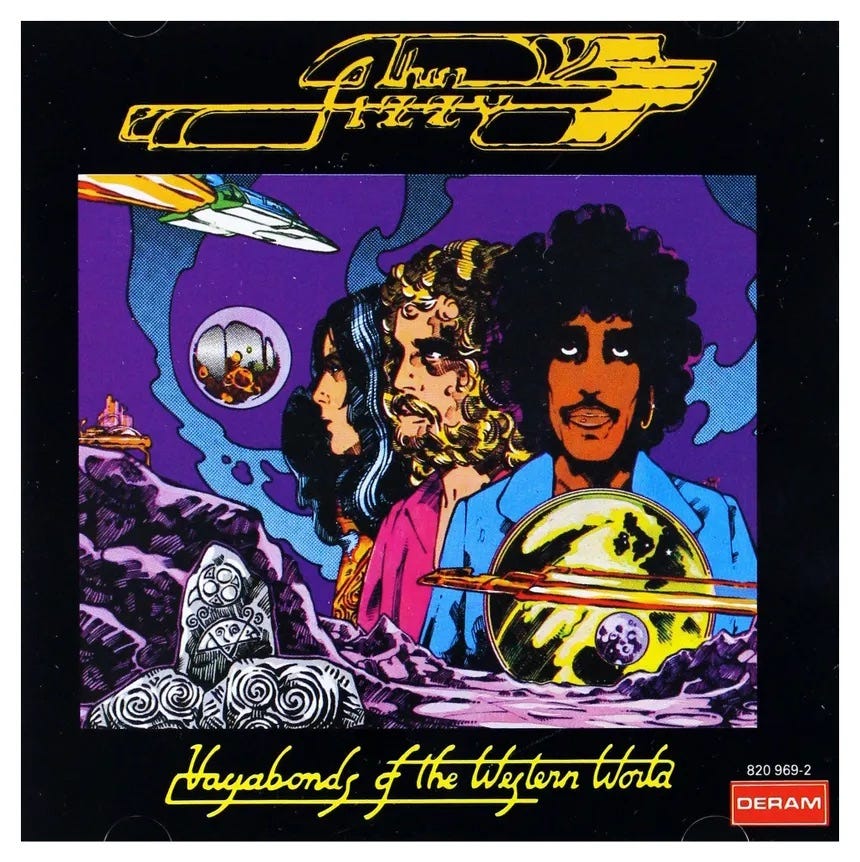

That’s where I first heard Vagabonds of the Western World, a scrappy, swaggering record by a band with an Irish name and a whole lot of bite. I loved that an Irish rock band was fronted by a tall and striking-looking black man, Philip Lynott, but it was really the whole package. In fact, the guitar tone caught me first—fluid but fierce, not flashy, just raw and honest. His name: Eric Bell.

Despite the album’s unevenness, it became one of my favorites and still holds up all these decades later. And like any young radio nerd, I wanted to get closer to the source. So for a class assignment, another student and I drove out to the Lake Oswego Elks Club, where KQIV had its studio tucked upstairs. We got to meet a couple of the voices we heard nightly, and in authentic '70s fashion, we even offered to share a doobie with one of them. He smiled, said thanks, but passed. It didn’t matter. We were in the room where the music happened.

That was my introduction to Thin Lizzy and Eric Bell, their original guitarist. Long before the twin-lead pyrotechnics of later lineups, Bell shaped the early sound: bluesy, gritty, and full of fire. His work on those first three albums helped set the foundation for what would become one of rock’s most legendary bands.

Eric Bell in His First Incarnation

This is a look back at Eric Bell—his music, his impact, and why his contributions still resonate, even if his name isn’t always top of mind when Thin Lizzy comes up.

Bell only played on Thin Lizzy’s first three albums: Thin Lizzy (1971), Shades of a Blue Orphanage (1972), and the aforementioned Vagabonds of the Western World (1973). I had to find Vagabonds to dig into it even deeper but since it was still a bit obscure (you didn’t find it in your local department store), so my buddy and I took the trip from Mt. Hood Community College, drive the 30 minutes west on Burnside to 32nd Avenue, where Music Millennium had set up shop recently. It was a gas, and we’d spend an hour at least before finally making our decision with our extremely limited funds. But I brought home the album and played it over and over.

It was a few years before I discovered the band’s first two albums, and ended up purchasing them, both of which turned out to be quite different than their third.

🎸 Finding Their Voice: Eric Bell and Thin Lizzy’s Early Evolution

Before Thin Lizzy stormed the charts with twin-lead guitars and arena-sized rock anthems, they were a band still figuring it out—stylistically, sonically, even spiritually. And right at the center of that search was Eric Bell. His guitar work was the constant thread weaving through three wildly different records, each one pushing the band closer to its breakthrough sound.

Their 1971 debut, Thin Lizzy, is intimate and genre-fluid. Bell's playing is understated and elegant—more conversational than commanding. The arrangements lean heavily on acoustic guitar, jazzy flourishes, and poetic lyricism. “Saga of the Ageing Orphan” and “Eire” feel more like Irish folk tales set to music than rock songs, and Bell matches that mood with delicate phrasing and tone. One hook-laden song, “Look What the Wind Just Blew In,” was full of great guitar work and hooks, but too odd to ever get played on the radio, much less released as a single. It’s an album best enjoyed while relaxing, allowing its multitude of colors to wash over you. It’s an album of shadows and sketches, and his guitar floats through it all like a subtle narrator.

The band became bolder with Shades of a Blue Orphanage (1972). Bell’s tone grew heavier, and the structures became more adventurous. From the funky strut of “Brought Down” to the orchestrated sweep of “Sarah,” you can hear the band testing boundaries. Bell’s guitar remains more textured than aggressive, but there’s a simmering intensity just beneath the surface—especially on “Baby Face” and “Buffalo Gal.” This was a band playing dress-up with genres, and Bell was the one stitching it all together.

Then came Vagabonds of the Western World (1973). That’s when everything clicked.

The album bursts with confidence, thanks in no small part to Bell’s unleashed guitar work. “The Rocker” serves as a snarling mission statement, and Bell plays as if he has something to prove—fuzzed-out riffs, searing solos, no holding back. “Gonna Creep Up on You” carries a swagger that was absent on the earlier records, while “Little Girl in Bloom” demonstrates their ability to deliver a soft punch with emotional precision.

Bell didn’t just keep up with this shift—he led it. His playing on Vagabonds was sharper, louder, and more dangerous. He brought the fire while Lynott brought the poetry, and together they built the blueprint for what Thin Lizzy would become.

And yet, Vagabonds would be his swan song with the band. Burned out from the road and the rock lifestyle, Bell left shortly after its release. But his fingerprints were all over their sound. Without Eric Bell, there’s no Thin Lizzy as we know it. His contribution is not just historical—it’s foundational.

Lyrics That Resonated

What struck me most about Thin Lizzy’s first three albums—Thin Lizzy, Shades of a Blue Orphanage, and Vagabonds of the Western World—wasn’t just the music, though that was compelling in its own right. It was the lyrics. Phil Lynott’s words had a kind of emotional x-ray quality, revealing heartache, loneliness, defiance, tenderness, and a restless searching that I felt deeply as a teenager and into my early twenties. Songs like “Saga of the Ageing Orphan” and “Sarah” weren’t just poetic but personal. They resonated with that confusing swirl of emotions I carried at the time: the ache of not quite belonging, the thrill and fragility of love, the sting of betrayal, and the bittersweet hope that came with dreaming big. Even the more theatrical or hard-edged songs carried that weight—stories of outsiders, romantics, and fighters. Lynott gave voice to feelings I hadn’t yet found the words for. Those albums weren’t just soundtracks to my youth—they were lifelines.

But Who Was Eric Bell? That Murky Era Before Google

Back in the '70s and '80s, trying to learn anything about a band was an exercise in patience and luck. There were no websites, no YouTube interviews, no Reddit threads. You picked up scraps where you could—liner notes, rock magazines, maybe a late-night DJ who knew more than he let on. And because of that, stories about musicians came to you half-formed, like myths.

I remember hearing that Eric Bell had mental health issues, and maybe that was why he left Thin Lizzy. But who really knew? It was just one of those things people said, and there was no real way to confirm it. What I did know was that he laid down some of the most electrifying guitar work I’d ever heard, especially on Vagabonds of the Western World. That was real. That was his.

As it turns out, Bell’s exit was dramatic—New Year’s Eve, 1973. During the gig, he hurled his guitar into the air, knocked over an amp, and walked offstage. In later interviews, he talked openly about why: the grind of touring, his own struggles with alcohol and drugs, and a personal life that was, in his words, a mess. Looking back, he’s said that if it had happened today, someone might’ve stepped in and given him time to recover. But in those days, there wasn’t a lot of room for that. You either kept up, or you burned out.

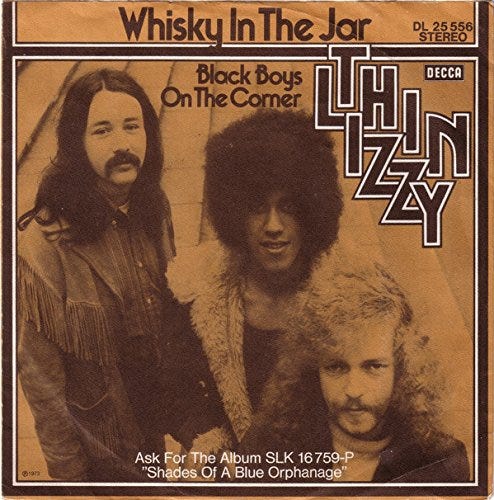

Two Lesser-Known Gems: “Black Boys on the Corner” and “Sitamoia”

Bell also played on a couple of early non-album tracks that remain timeless.

“Black Boys on the Corner” was the B-side to “Whiskey in the Jar,” and it's a gritty, riff-heavy track that shows a different side of the band—more streetwise, more attitude. Bell’s guitar bites and snaps, full of energy and swagger.

“Sitamoia” is a bit more elusive. It appeared on the "Remembering – Part 1" compilation, and it has also appeared on at least one other compilation I have. And while there’s been some debate over who wrote it—some say Lynott, others say Brian Downey—the guitar work is unmistakably Bell. The song itself draws from an old Irish tune called “Cailleach an Airgid” (“The Hag with the Money”), tying right back into the band’s roots.

Together, these two songs—along with the first three albums—paint a vivid picture of a band still forming, still experimenting, and of a guitarist whose fingerprints were all over that evolution.

🎶 Life After Lizzy: Eric Bell’s Post-Band Journey

In researching this article, I learned a bunch of things about Eric Bell I didn’t know—and one of them surprised me the most: he’s still kicking. Still playing. Still making music.

For some reason, I had it in my head that he’d passed away, but nope. Eric Bell, at nearly 78, continues to perform occasionally and has quietly built a body of solo work that deserves more attention.

After leaving Thin Lizzy in late 1973, Bell stepped away from the chaos of touring and the rock-and-roll lifestyle that had nearly burned him out. But he didn’t stop making music. In the mid-70s, he joined forces with former Jimi Hendrix Experience bassist Noel Redding in the aptly named Noel Redding Band. Bell played guitar on two of their studio albums—Clonakilty Cowboys (1975) and Blowin’ (1976)—both of which have that shaggy, mid-decade blues-rock feel. A third record, The Missing Album, featuring unreleased tracks from that same era, was released in 1995.

Beyond that, Bell quietly carved out a solo career. Albums like Exile (2015) and Standing at a Bus Stop (2017) show a bluesier, more reflective side of his playing. There’s a sense of space and soul in his later work—no flash or pyrotechnics, just tone and storytelling. You get the feeling these songs were written in small rooms with big memories.

Even now, you can occasionally find him on stage in Ireland or the UK, playing pub gigs or small festivals. No fanfare. No arena lights. Just a Strat, a few pedals, and that unmistakable touch.

For a guy whose early riffs helped define one of rock’s most legendary bands, Eric Bell never chased the spotlight. But he’s never stopped chasing the music.