Norman Seeff’s Studio Magic

From album covers to live audiences, the unconventional methods behind the images we can’t forget.

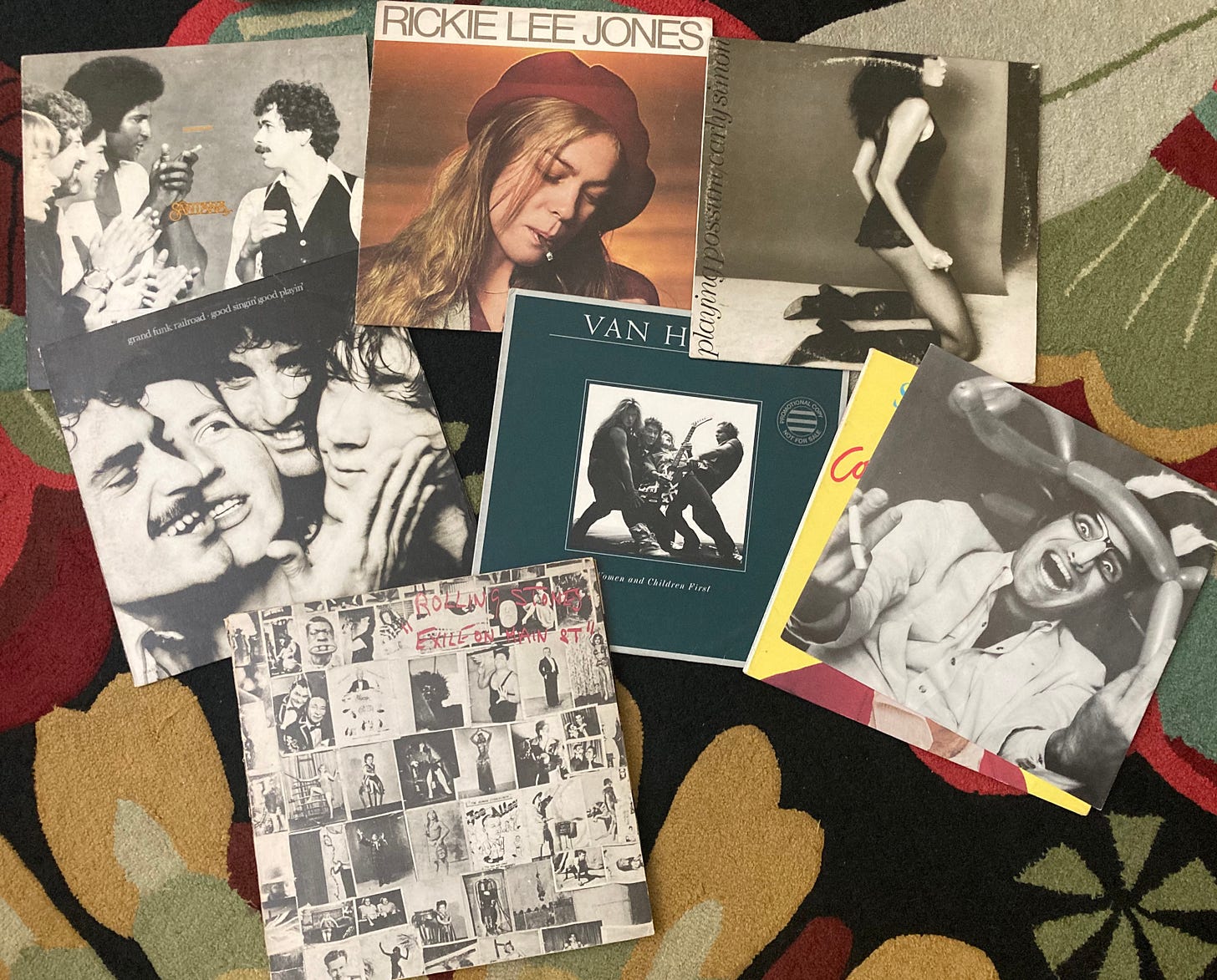

Early in my radio career, the station was flooded with hundreds of new albums every month. There was no way to listen to them all, but I always made time to flip through the covers and check the back. After a while, certain visual styles started to stand out. One name kept appearing: Norman Seeff. Before long, I didn’t even need to see the credit—his work had such a distinct feel that I could almost always spot it at a glance. Van Halen’s Women and Children First, Carly Simon’s Playing Possum, Joni Mitchell’s Court and Spark and Hejira, Earth, Wind & Fire’s That’s the Way of the World, and the Eagles’ One of These Nights all carried his unmistakable touch.

I wasn’t sure what stood out about his images. Perhaps it was the lighting, or the spare background—like the simple backdrop and the edge of the studio on the Playing Possum cover. Or the black-and-white double exposure on Joni Mitchell’s Hejira. He seemed to work often in sepia tones, although he wasn’t opposed to showing flashes of bright and bold colors now and then.

I also recall the image on Steve Martin’s “Let’s Get Small,” and I instantly knew that Seeff had taken it. The more I looked, the more I recognized a pattern: almost all of these portraits were shot in a studio, not on location. This meant the stars and performers would be in his space for hours—maybe an entire day. As a photographer, I knew that taking hundreds, even thousands, of frames in a session wasn't unusual; somewhere in that process, one image would emerge as the image.

Since this was the ’80s, it was next to impossible to stumble across articles detailing how Seeff ran his sessions. Years later, I was fascinated when I finally learned how he approached them.

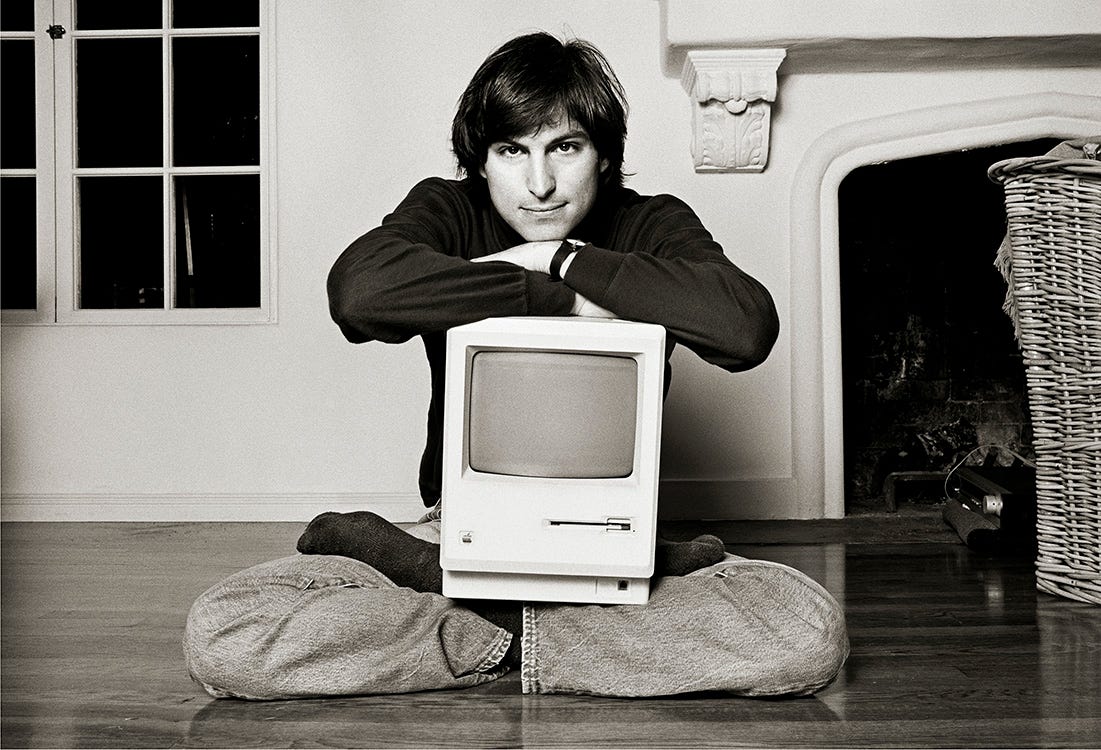

One of the best examples came from his 1984 session with Steve Jobs, just weeks before the Macintosh was launched. Seeff didn’t arrive with a rigid shot list—he arrived to talk. Jobs’s living room in Woodside was almost bare, so they sat and discussed creativity, ideas, and the nature of innovation. As the conversation deepened, the tension and self-consciousness fell away. Then, mid-sentence, Jobs left the room, returned carrying the unreleased Mac, and without prompting, sat cross-legged on the floor with it in his lap.

Seeff didn’t rearrange him or adjust the concept—he simply followed the moment, shooting as it unfolded. They kept talking, moving, and experimenting, even lying on the floor drinking beer as Seeff kept the camera rolling. There was no performance for the lens, just an authentic connection between two creative people exploring ideas. That now-iconic “Mac on lap” photo was captured in that spontaneous moment, proof of Seeff’s philosophy that the best images come when the guard drops and something real surfaces.

If the Jobs session was a quiet, cerebral dance, the Tina Turner shoot was pure kinetic fire. By the time they worked together in 1983, Seeff had already photographed her once before with Ike in the mid-’70s. This time, it was just Tina—confident, free, and on the brink of her massive solo comeback.

From the moment she stepped into his Los Angeles studio, the energy shifted. Seeff described working with her as “being exposed to a nuclear reactor.” He wasn’t just photographing her; he was trying to keep up. She moved constantly—dancing, laughing, striking poses, throwing herself into the music that played in the background. Seeff shot so fast that he actually blew his strobe during the session, but neither of them stopped. He kept photographing in available light while the film crew documented everything, capturing the raw electricity between them.

The results were the “Bel Air Sequence”—a series of images bursting with motion and charisma. They weren’t about a single perfect pose; they were about the cumulative impact of a living, breathing performance that happened in front of the camera. As with Jobs, Seeff didn’t impose a rigid plan. He created the conditions for something authentic and unforgettable to emerge, then let the subject’s own creative energy take over.

Seeff, who was born in South Africa in 1939, became a medical doctor in 1965. Three years later, he emigrated to the US to pursue his creative passions. He aimed his camera at people on the streets of New York City, until he met graphic designer Bob Cato, who introduced him to rock photography. It lit a spark in Seeff, and he found that working with creators and performers, the sessions became opportunities to explore the visual side of their art.

Seeff’s reach went far past album art. Over decades, he applied the same empathetic, slow-burn energy to icons like Andy Warhol, Ray Charles, Sir Francis Crick, and filmmakers such as John Huston and Martin Scorsese. He even brought his approach to commercials—filming ads for brands like Apple and Levi’s—always holding onto the conviction that trust and creative flow were the true subjects of the image. It wasn’t just about capturing icons; it was about inviting their humanity to show up under the lights.

Where Is Norman Seeff Now?

As of this writing, Norman Seeff is 86—and still very much a presence in the creative world. While it’s unclear if he’s conducting new photo sessions, he remains active through exhibitions, talks, and digital projects that showcase his vast archive.

In 2025 alone, his work has been the subject of two major exhibitions: “50 Years X 50 Icons” at Kamil Art Gallery in Monaco, and “Homecoming” at the Norval Foundation in Cape Town, South Africa. Both shows featured his iconic portraits and rare video footage from his filmed sessions—offering a window into the dynamic, collaborative process that made his work so distinctive.

Seeff still works out of his Burbank studio and describes himself as an “explorer of the creative process.” He’s currently preparing a multi-media, multi-disciplinary release of his archive for interactive digital platforms. Even in his ninth decade, Seeff’s focus remains on the same core mission that’s defined his career: capturing authenticity, connection, and the spark of creation.

I can safely say that Norman Seeff’s photography has made a lasting impression on me. His work has inspired me and shown what’s possible when creative minds truly collaborate in the art of image-making. More than just portraits, his photographs are living records of connection, spontaneity, and trust. And in the world of imagery—especially within the rock and roll canon of the ’70s and ’80s—his influence is indelible, etched into the visual memory of an era