Johnny and the Distractions: What Happened to "Let It Rock"

Forty Years Later, the Untold Story Behind the Band's Major Label Debut

Introduction

On New Year’s Day, I published an article about Johnny and the Distractions’ legacy, reflecting on a Portland band that seemed headed for national success in the early ’80s. That piece was written from memory — bits and pieces I’d collected over the years — and was primarily meant as an homage to the band and the city they sprang from.

Yeah, I was a big fan. I’d attended countless performances, from sweaty basement bars to one of their early breakthrough gigs, when they opened for Loverboy at Portland’s Paramount Theatre. For those of us who followed the band closely, it felt like they were on the verge of hitting the big time. And if that was the case, anything seemed possible.

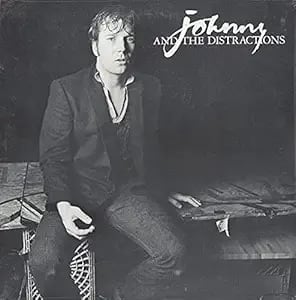

Central to that story was Let It Rock — the band’s major-label release on A&M Records. The album earned strong radio adds, built a wave of early momentum, and hinted at big things to come.

And then, just as quickly, it all seemed to stall. I was a Top 40 Music Director in the late 70s and early 80s, and seeing a fresh new artist’s song get noticed, and then fade away was not unusual. These things happen. Competition is intense, and there’s always something new right around the corner. Usually, those of us in the industry without insider knowledge chalk it up to the whimsy of the marketplace. Nothin’ you can do about it except shrug, wish things had worked out better, and move on.

In the weeks after Let It Rock hit the airwaves, the record became hard to find in stores, especially outside the Northwest. David Kershenbaum, the A&M executive who signed and produced the band, left the label shortly after the album’s release. And the big breakthrough that had seemed inevitable never arrived.

To understand why, I spoke with two people who lived it: Jon Koonce, the band’s frontman, and Terry Currier, longtime owner of Music Millennium and co-founder of Burnside Records. What emerged was fascinating — two people with great respect for each other, recalling the same events from different vantage points.

How the Story Came to Me

In May of this year, Jon messaged me on Facebook, saying he’d be in Oregon for a few weeks and that it wouldn’t be an imposition if I called him. He included his phone number.

I was curious about the message — after all, I’d only met Jon a few times, back in the ’80s when I had him on my radio show at KKSN-FM in Portland. Why was he reaching out now? And why me?

When I called, Jon explained that his wife had come across my earlier article. He said he thought it was a good piece — not full of the misinformation he’d seen elsewhere — and if I wanted to know the real story behind Let It Rock, he’d be glad to tell me. As he put it, most of what’s out there is “complete BS.”

How could I say no?

We tried to set up a meeting while he was in Oregon, but when that fell through, we agreed to talk by phone after he returned home to North Carolina. Over the next couple of months, we had several long conversations.

This is the story Jon told me.

Act I — Rising Stars

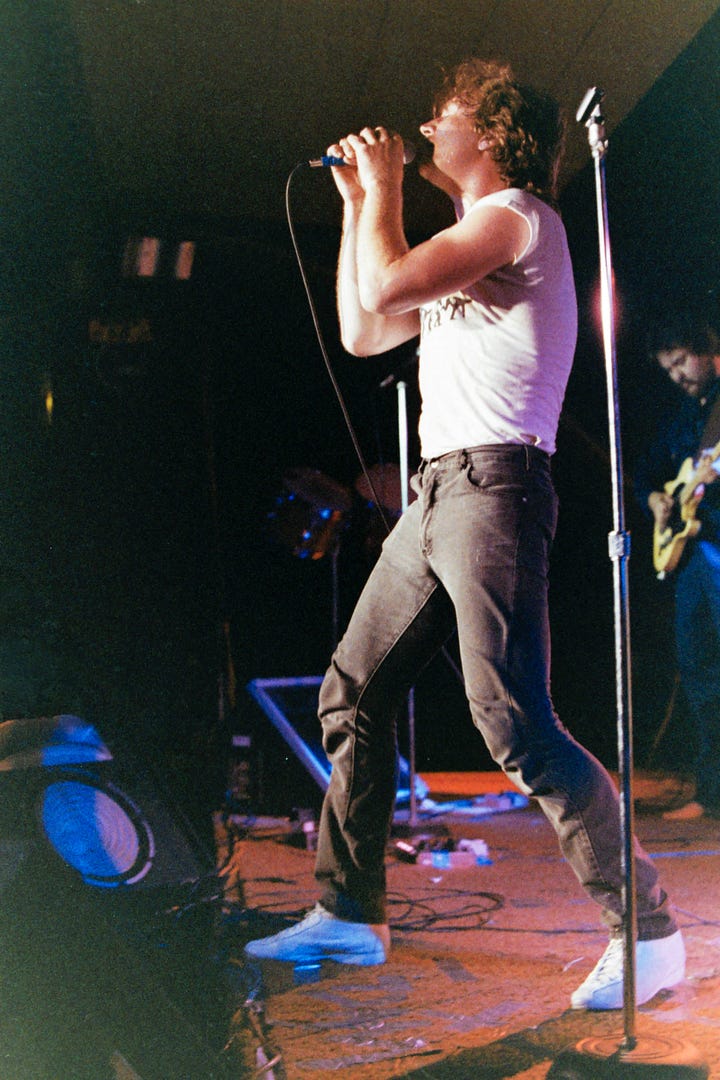

By the late 1970s, Johnny and the Distractions had become one of Portland’s hottest live acts. Their shows were sweaty, high-energy affairs, the kind where Jon left everything he had onstage. Some fans even compared him to Bruce Springsteen — not a bad comparison, given the heart-on-sleeve songwriting and relentless performances.

The band’s self-produced “black-and-white” 1980 debut album built a strong regional following and landed airplay up and down the West Coast — 15 to 20 stations, despite having no label support. That momentum caught the attention of A&M Records.

Kershenbaum, then A&M’s head of A&R, sent his assistant Jordan Harris to Portland to see the band at Sack’s Front Avenue, a Thursday-night gig arranged specifically for his visit. Sack’s was one of Portland’s go-to clubs for rising acts, hosting bands like Seafood Mama (soon to become Quarterflash), Robert Cray, Billy Rancher, Sleazy Pieces, and Upepo. Harris was impressed and urged Kershenbaum to sign the band.

Within weeks, Jon and the Distractions had a contract and their shot at the big leagues.

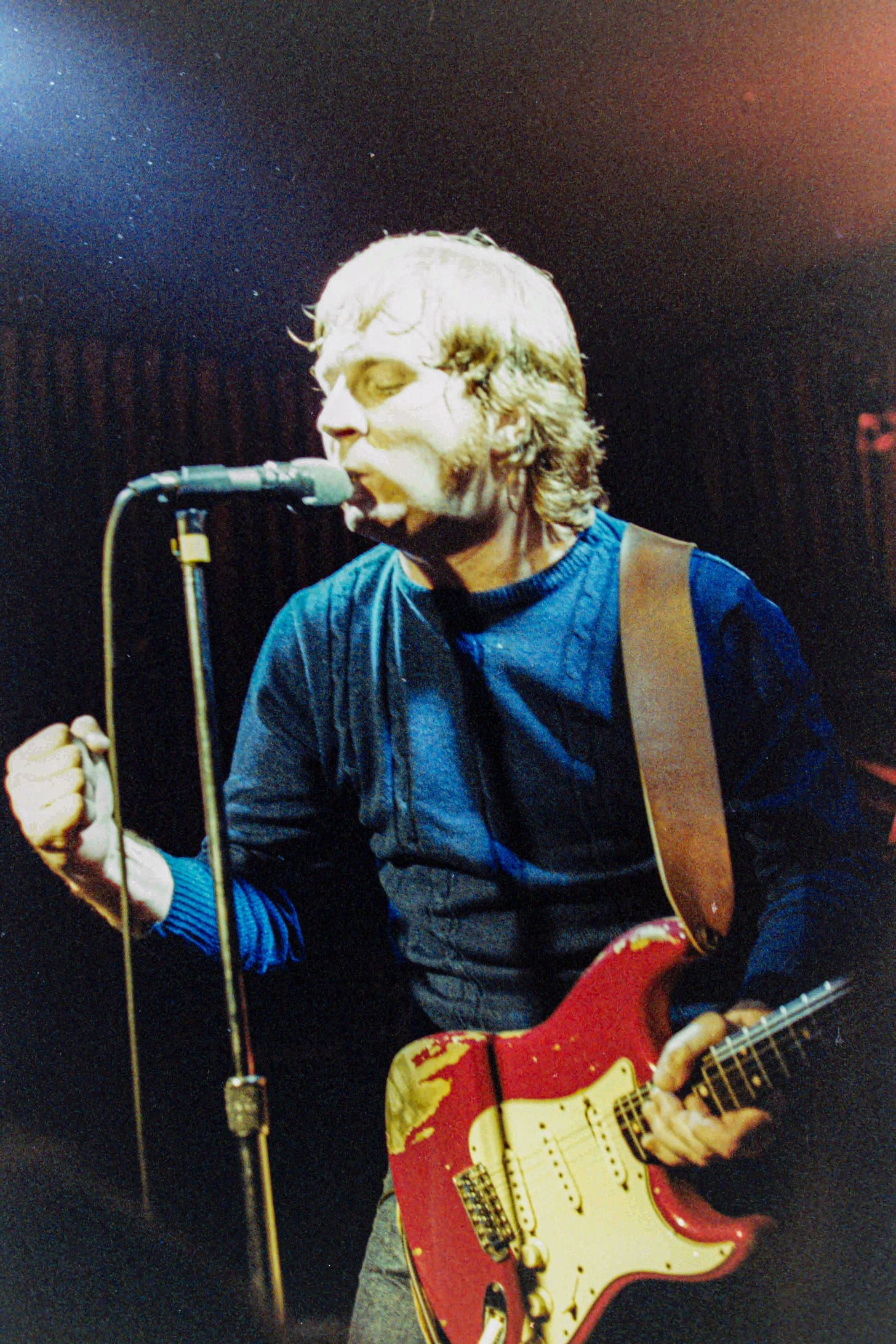

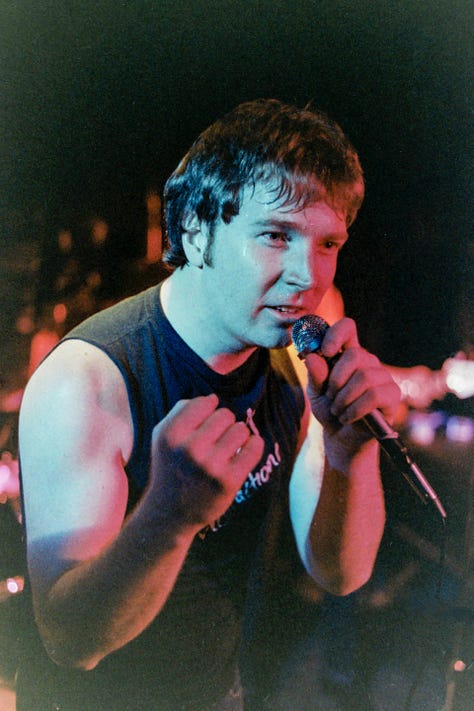

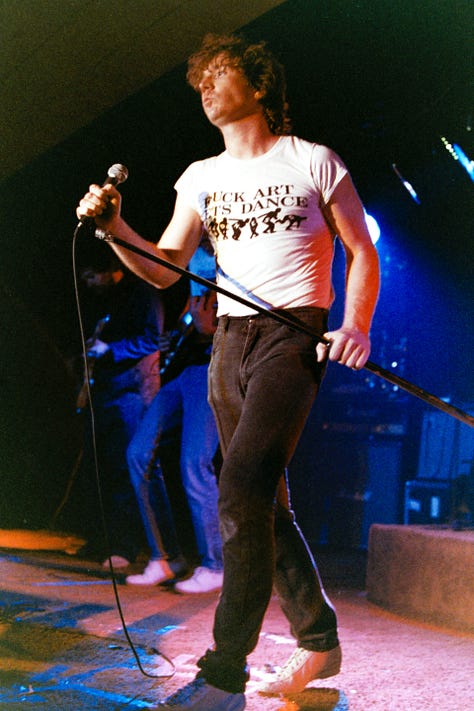

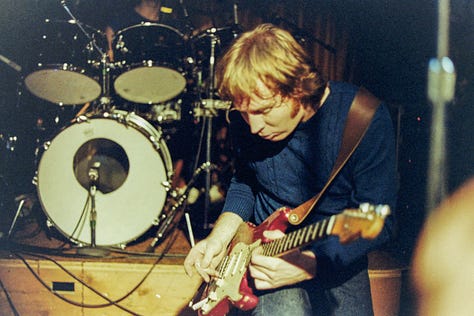

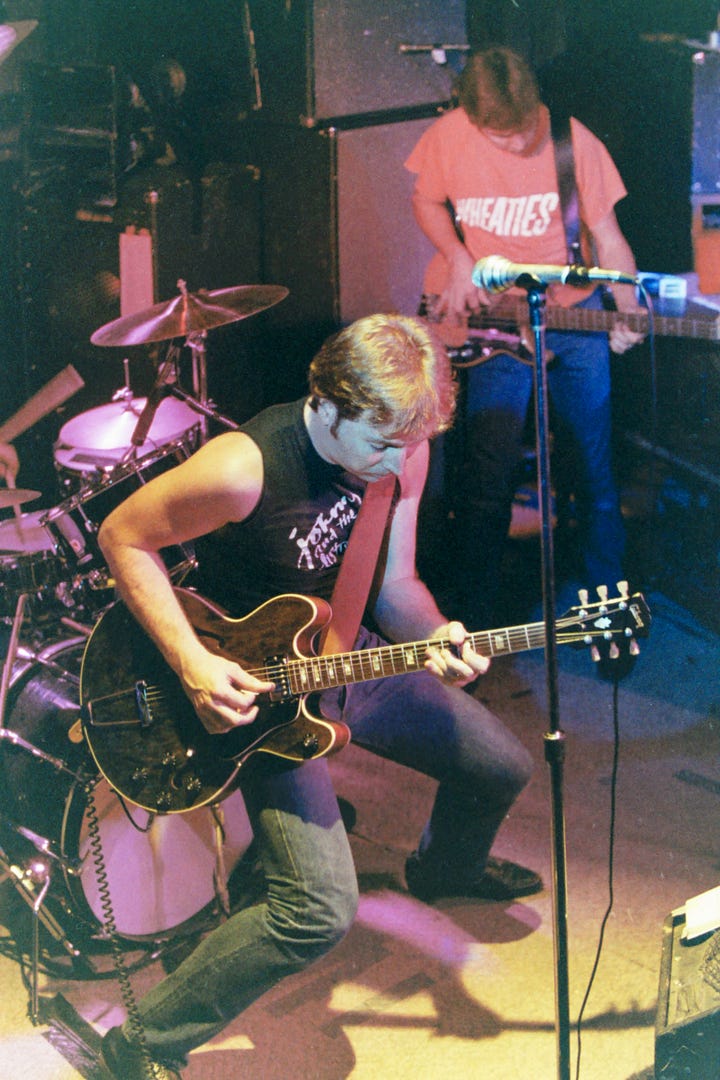

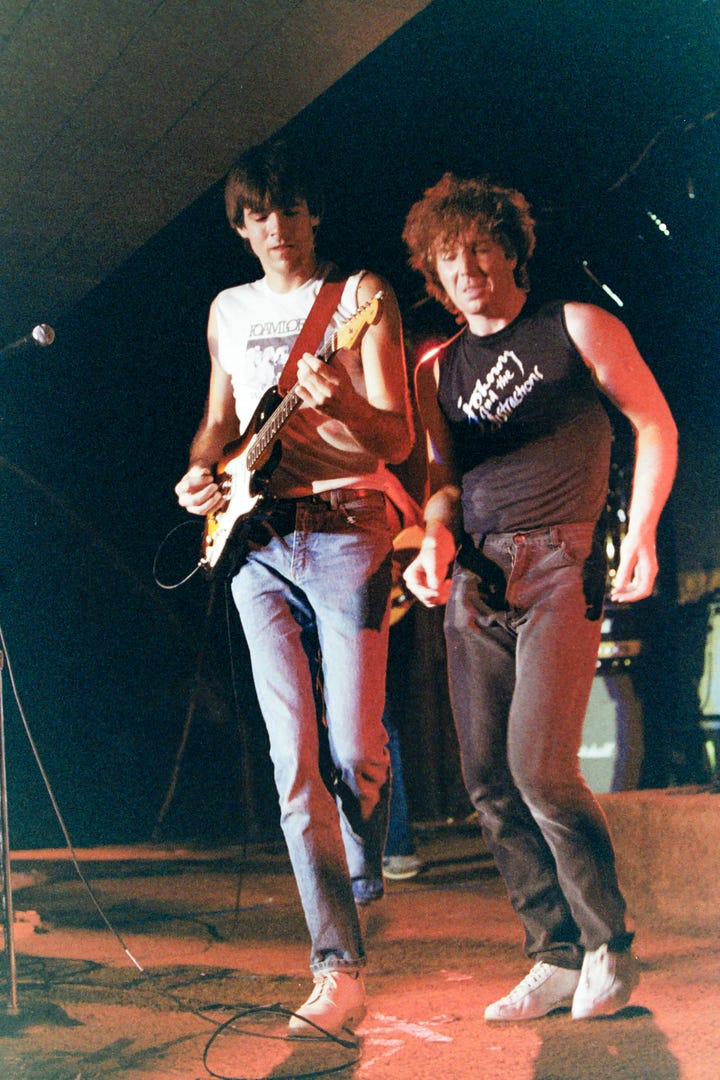

Shot of Johnny and the Distractions from the early 80s.

Act II — Making Let It Rock

In the fall of 1981, the band headed to Los Angeles to record their major-label debut with Kershenbaum producing.

Jon recalls quickly realizing that Kershenbaum wasn’t going to guide the band in the way he expected. “He didn’t play an instrument, didn’t read or write music,” Jon said. “After three days of watching him eat watermelon, smoke weed, and do sit-ups, we finally just picked up our instruments and started rolling tape.”

With little direction from the producer, the Distractions leaned on the instincts they’d honed playing hundreds of shows. Most of Let It Rock was recorded “live off the floor,” giving the album a raw, immediate feel that set it apart from the slick productions dominating early-’80s rock radio. Jon told me that, as good as the ‘black and white’ album was, he liked “Let it Rock” better: “It captured our sound.” One track, City of Angels, even features a scratch vocal recording using a $100 Shure SM57 microphone — a take Jon never intended to use but which carried so much energy it became the keeper.

Tensions in the Control Room

After recording wrapped, the team flew to Media Sound on West 57th Street in Manhattan — a legendary studio just blocks from Carnegie Hall — to overdub final vocals and mix the album.

That’s when Johnny and the Distractions’ co-manager John Bauer invited his “drinking buddy,” Lee Michaels, to sit in. Michaels wasn’t just a friend — he’d been Program Director at Seattle’s KISW-FM before joining Burkhart, Abrams, Michaels & Douglas, the powerful consulting firm shaping Album-Oriented Rock playlists nationwide. Dozens of nationwide rock stations relied on BAM&D’s guidance, making Michaels’ opinions carry serious weight. (Note: Lee Michaels was not the Michaels named in the firm; that was a gentleman named Don Michaels.)

Jon remembers Michaels as “a very opinionated guy” who offered nonstop critiques of the mix. He says Michaels’ presence “intimidated David to no end,” and Kershenbaum “couldn’t really tell him to back off because of who he was.” At one point, Jon quietly pulled Bauer aside and suggested easing Michaels out of the room — they didn’t want to “burn a bridge” with someone so influential.

It was a moment where the politics of radio, management, and label expectations collided in the same room. For Jon, it underscored just how many outside forces were shaping the fate of Let It Rock — and how little control the band ultimately had over its own record.

Act III — Release and Stall

The rollout looked promising when Let It Rock was released in early 1982. In its first week, the album was added to 60 stations nationwide, tying with Huey Lewis & The News’ sophomore effort, Picture This, as the most-added album in the country. Within weeks, it was spinning on more than 150 stations.

“Everyone said, ‘Congratulations, your life just changed,’” Jon recalled.

But just as quickly, the momentum slowed.

On tour opening for acts such as Asia and The J. Geils Band, Jon started calling record stores in city after city — and kept hearing the same thing: they didn’t have the album, or had never received it.

Around the same time, David Kershenbaum left A&M, and Jon says the label’s support evaporated almost overnight. Jon shared an interesting story about the record and airplay in Portland at that time. For instance, KGON, Portland rock station, was not playing the record, and as a result, Lee Michaels called up the Program Director and read him the riot act, saying he had to get on board with a band that was going places.

Later, when his solo album “Got My Eye on You” came out, something odd happened at another Portland radio station when he was invited to do an on-air promo piece for the new album. “And there was this absurd little promotion that went on for a few minutes where, yeah, ‘Jon Koonce is here. He's got a new album out, you know, yeah, it's round, and it's got a little hole in the middle. We can't play it. But wow, the cover looks really good, Jon, that's a nice picture of you.’”

Act IV — Conflicting Memories

According to Jon, the explanation came later, and it came from Don McLeod, co-owner of Music Millennium and Burnside Records. Jon shared a particular memory of when McLeod saw him in the store one day and invited him up to the office, a serious look on his face. McLeod told him that after Kershenbaum left A&M just weeks after the album’s release, the label effectively stopped supporting it. “What Don told me, “I think you need to know this. You don't know what A&M did. This is not an accident. They shelved the record.”

While Jon believes strongly that Let It Rock was intentionally shelved, Currier recalls it differently. Terry remembers steady reorders in the Northwest and says the album remained in print for a while.

Act V — Burnside Records Steps In

By the mid-to-late ’80s, even though “Let it Rock” and “Got My Eye on You” didn’t take off nationally, there was still enough demand for Johnny and the Distractions’ music that Burnside Records wanted to make something happen.

According to Jon, Don McLeod told him he’d approached A&M about licensing the Let It Rock masters for a reissue but was turned down flat. Which he found surprising: “Who turns down free money?”

Burnside Records pivoted to a new plan: take the band back into the studio and re-record several tracks from Let It Rock and new material.

Burnside flew Distractions Mark Spangler up from Los Angeles to play guitar and hired Bob Stark as the engineer — “still the greatest engineer Portland’s ever seen,” Jon said. The sessions were held at Sound Impressions, one of Jon’s favorite studios.

Jon admits he was unsure about revisiting the material at first, but the timing — and the escape — made sense:

“They were paying for it, and I could go into the studio of my choice, where Bob Stark was the engineer, and I could spend a couple of weeks working on this record… or I could sit around the house and wallow. I chose the studio — a bunch of cool tube amps and guitars beat the alternative.”

The result was a new Burnside release that gave longtime fans access to many songs they loved — even if they weren’t the original A&M masters.

For Jon, though, A&M’s refusal to license Let It Rock still stung. It felt like a final reminder of how the album’s promise had been squandered.

Epilogue — Legacy

Forty years later, Let It Rock remains a beloved record for those fans who packed the clubs, called the stations, and wore out their vinyl copies.

The full story of what happened behind the scenes may never be resolved. But the music endures, along with the mystery. And for Johnny and the Distractions, that’s its own kind of legacy.

When the band called it quits, Jon soldiered on, making music for decades with a handful of musicians, recording several terrific albums — lots of rock, some ballads, and plenty of rockabilly. All worth a listen.

These days, Jon’s retired and living in North Carolina. He’s self-published a pair of books — raw, funny, and heartfelt, much like his music — and a third is in the works, though he admits it’s “slow-going.”

Looking back, you can trace the thread from a kid sneaking into Big Reggie’s Danceland on Lake Minnetonka in Excelsior, Minnesota, to catch the Everly Brothers, to standing wide-eyed at the Beatles’ first U.S. concert in ’64 in Washington, DC (thanks to his mother’s connection at a newspaper), all the way to the Let It Rock sessions and beyond. That early spark — watching his heroes sprint onto a stage and make magic out of chaos — never went out. It carried him through the Distractions, through decades of songwriting, and it’s still there, humming in the background.

Maybe that’s the real legacy of Johnny and the Distractions: the music, the grit, and the belief that rock and roll — once it gets its hooks in you — never really lets go.

Thanks to Jon and Terry for sharing their stories. Thanks to Johnny and the Distractions for playing great rock and roll music that left its mark on countless fans.

Photographs by Tim Patterson, taken at a handful of gigs in the early to mid-80s in Portland.