Vortex by Catherine Coulter: a Review of Sorts

What happens when two storylines refuse to connect?

I’m unfamiliar with Catherine Coulter’s extensive list of published books, including many best-sellers. But I at least recognized her name when I ran across Vortex last month at a library book sale, and since it was the last day of the sale when a bag of books cost just $5, it was a good find.

I just finished the book and enjoyed it. She has a great sense of pacing and includes enough detail—sometimes too much for my taste—but the story moves forward at a good clip.

However.

About halfway through the book, I started to wonder about something. What might that be? Here’s a clue -- the book flap description of the contents:

Seven years ago Mia Briscoe was at a college rave with her best friend, Serena, when a fire broke out. Everyone was accounted for except Serena, who was never seen nor heard from again. Now an investigative journalist covering the political scene in New York City, Mia discovers old photos taken the night of Serena's disappearance and begins to uncover a sinister string of events going all the way back to that disastrous party. Working with Sherlock, the secrets begin to unravel.

But some very powerful-and very dangerous—people will do anything to keep them from learning the truth.

CIA Operative Olivia Hildebrandt is a team leader on a mission in Iran to exfiltrate a betrayed undercover operative. She's nearly killed by an exploding grenade and saved by a team member. But by the time Olivia is released from Walter Reed Hospital, that team member and a critical flash drive he was carrying have disappeared. When Olivia is savagely attacked on her first night home, Savich suspects that the strike is a direct result of the compromised mission and the missing team member and flash drive. But what intelligence was at stake and who betrayed them?

Okay, that’s all fine and dandy. We’re following reporter Mia Briscoe and the story of her friend from seven years back. And we’re also on the trail of Olivia Hildebrandt, the CIA op who recently returned from Iran.

When shall the twain meet? Never. Not at all. The two stories ran concurrently, side by side, but each in parallel universes. It was as if the other story—in the same damn book—was not necessary to the one you were reading.

I kept thinking that Coulter would connect them, but that was untrue. By the time I was about ¾ of the way through, I had determined that the stories were independent and had nothing to do with each other.

I’m sure I’d never read a novel with parallel stories that never met. Sure, some novels start out following one protagonist, then jump to a second figure, and eventually, you see the stories intertwine in some heroic fashion.

Not this one. Which got me thinking. Why? I had no answer, so I did what any self-respecting, curious author would do. I asked ChatGPT. Here’s what I received back:

That structure—two distinct stories running in parallel without overtly intersecting—is uncommon but not unheard of. It offers a fascinating narrative style that can explore contrasts, parallels, or thematic resonances. Here are some examples of novels with a somewhat similar approach:

"Cloud Atlas" by David Mitchell

While the stories in Cloud Atlas do intersect thematically and sometimes directly, they are structurally distinct, spanning different genres, eras, and characters. Readers experience them as separate stories that reflect on one another rather than directly converging.

"The Hours" by Michael Cunningham

This novel tells three parallel stories about women in different time periods, linked thematically through Virginia Woolf's Mrs. Dalloway. The characters do not interact, but their lives echo one another in profound ways.

"Pulp" by Charles Bukowski

This novel intertwines two different narrative threads: a parody of detective fiction and Bukowski's characteristic musings on life and death. The stories feel separate but coexist under a shared existential lens.

"A Visit from the Goon Squad" by Jennifer Egan

Egan’s novel is a collection of loosely connected chapters, each focusing on different characters and moments in time. While there are tangential connections between the stories, they often feel like standalone vignettes rather than a single cohesive narrative.

"If on a Winter's Night a Traveler" by Italo Calvino

This experimental novel alternates between two distinct narratives: the story of "you," the reader, and fragments of various unrelated novels that you begin but never finish. Each "story" stands on its own, creating a sense of disjointed parallelism.

"The Bridge" by Iain Banks

This novel alternates between two seemingly separate narratives: one set in a realistic world and another in a surreal dreamlike realm. The connection between the two is subtle and left partially open to interpretation.

"Blindness" by José Saramago and "Seeing" by the same author

These two novels are distinct but connected, examining different perspectives of societal collapse. While they're separate books rather than combined into one, they share a thematic resonance that mirrors the effect you're describing.

"American Pastoral" by Philip Roth

The novel weaves two distinct narratives: one about the life of Seymour "Swede" Levov, and another about the narrator, Nathan Zuckerman, who is trying to reconstruct the Swede's life. While these stories overlap, they are distinct enough to feel like two parallel threads.

Catherine Coulter's approach in Vortex sounds particularly unique if the stories truly do not meet or connect, as most examples like the above rely on some thematic or structural overlap. It’s an intriguing choice that can challenge conventional expectations of a novel. If you find another example like this, it’d be exciting to discuss!

In a sense, it opens up possibilities for writing fiction if a famous and successful novelist can successfully write a story with two distinct storylines that don’t intersect, except that the FBI is involved with both stories. Other than that, I saw nothing that would tie them together. The FBI agents featured in one storyline didn’t appear in the other (unless I missed it, which I suppose is possible).

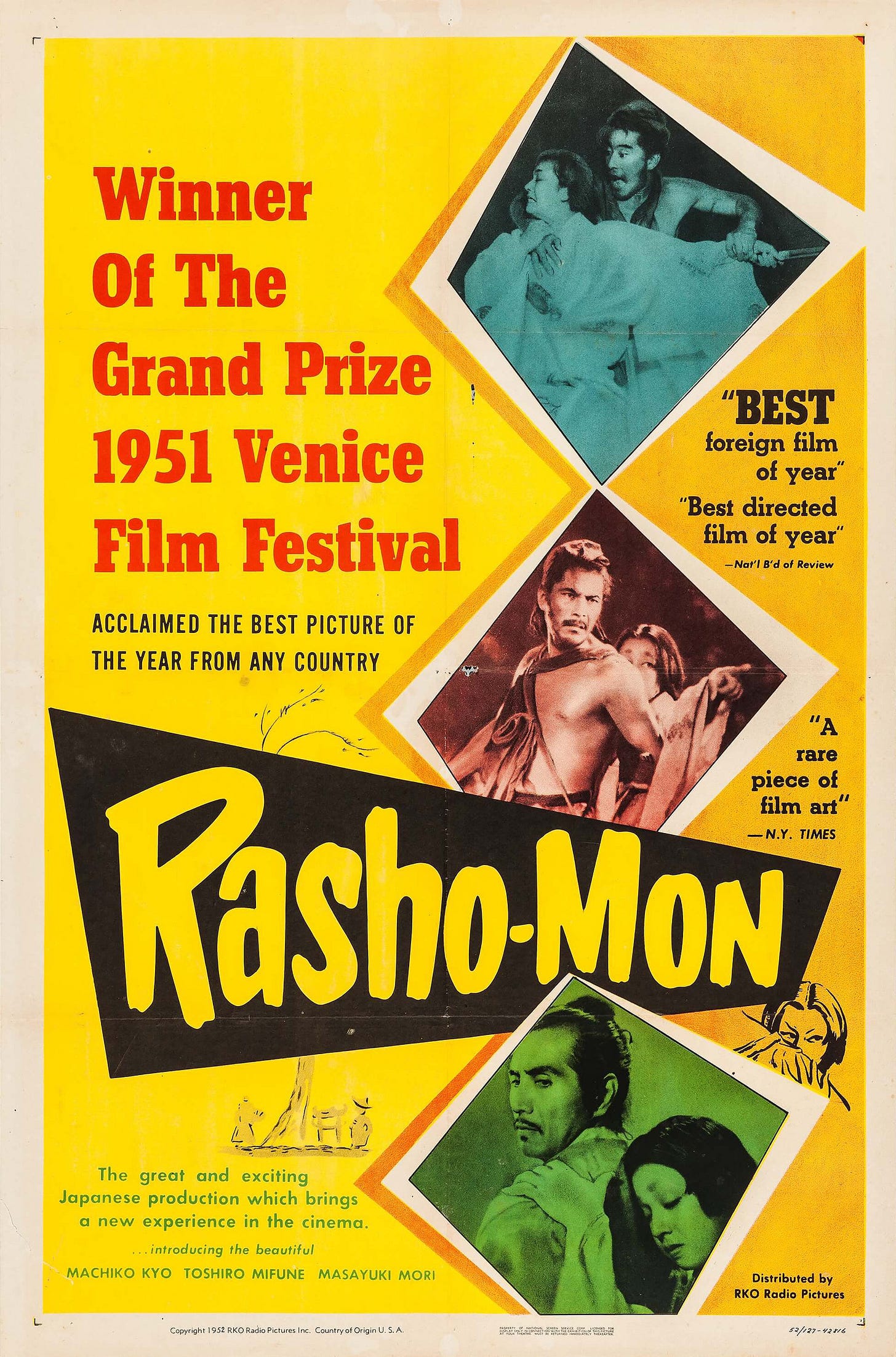

The novel reminded me, to an extent, of the famous movie "Rashomon" (1950), directed by Akira Kurosawa. It's one of the most famous films in world cinema and a landmark in storytelling. "Rashomon" tells the story of a violent incident—a murder and a possible assault—through the perspectives of four different characters: a bandit, a samurai (through a medium), the samurai's wife, and a woodcutter who claims to have witnessed the event. Each version of the story is drastically different, shaped by the narrator's biases, motivations, and self-perceptions.

The movie develops several themes, among them:

Subjectivity of Truth: The film delves into how personal perspectives and self-interest distort reality.

Unreliability of Memory and Testimony: It questions whether an objective truth can ever be known.

Human Nature: The different accounts reveal as much about the storytellers as the actual event.

Rashomon, as the term "Rashomon Effect," has since entered popular discourse, describing situations where different people offer contradictory interpretations of the same event. Its narrative structure has inspired countless films, books, and TV episodes, including Gone Girl, The Last Duel, and specific episodes of The X-Files or Lost.

To sum up, there are a hundred different ways to spin a yarn. The fact that Catherine Coulter’s Vortex managed to become a best-seller with two distinct and separate storylines was a revelation of sorts, and since I finished the book, I haven’t been able to get it out of my mind. Yeah, it’s gotten me thinking about what the possibilities might be for my future writing experiments.